- 13

- May

- 2025

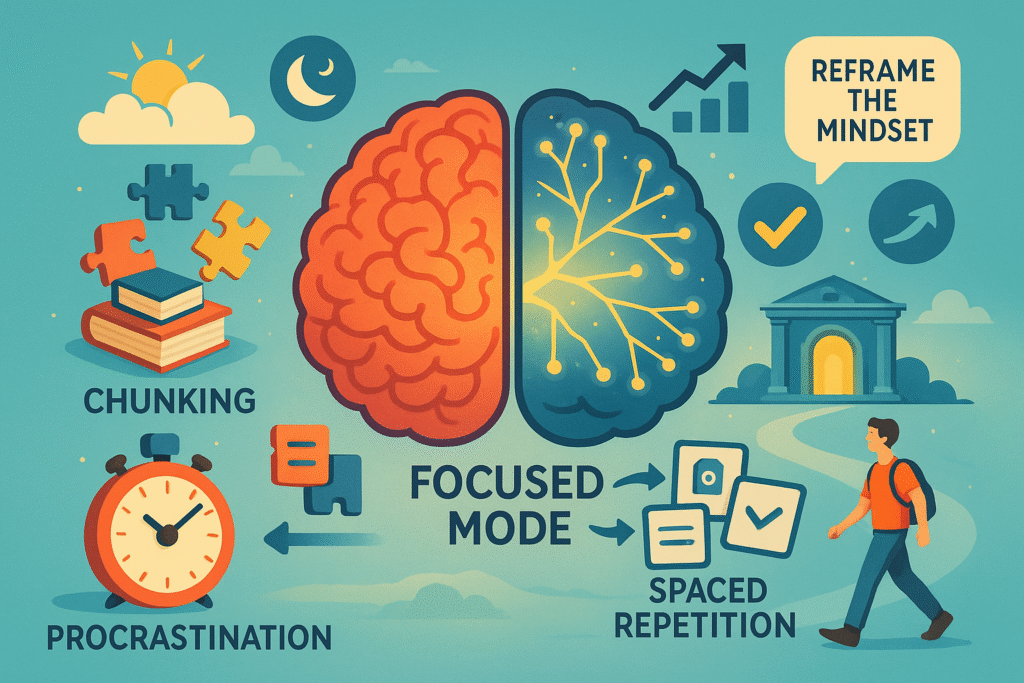

Core Strategies for Effective Learning

Core Strategies for Effective Learning

Summary:

This document synthesises key concepts related to effective learning, drawing upon excerpts from a teacher guide, lecture transcripts, an infographic, and a cheatsheet associated with the “Learning How to Learn” course by Barbara Oakley and Terrence Sejnowski. The sources highlight the importance of understanding basic brain functions, utilising different modes of thinking, managing procrastination through process-oriented techniques, and employing various memory strategies. Core themes include the distinction between focused and diffuse thinking, the concept and formation of ‘chunks’ of information, the detrimental effects of illusions of competence and overlearning, the value of spaced repetition and recall, and practical strategies for tackling procrastination and improving test performance.

Key Themes and Important Ideas:

- Focused vs. Diffuse Modes of Thinking:

The brain operates in two fundamentally different modes of thinking: the Focused mode and the Diffuse mode.

The Focused mode is associated with intense concentration on a specific learning task. It’s likened to a pinball machine with closely spaced bumpers, allowing thought to move smoothly along familiar neural pathways related to concepts you are already familiar with.

The Diffuse mode is a more relaxed thinking style related to neural resting states. It’s represented by a pinball machine with widely spaced bumpers, allowing thought to travel a long way before being interrupted, facilitating the exploration of new neural connections and big-picture perspectives.

Effective learning requires moving back and forth between these two modes. When stuck on a problem in the focused mode, shifting to the diffuse mode (through activities like walking, showering, or even sleeping) can help uncover new insights and solutions. This is exemplified by the anecdotes of Salvador Dali and Thomas Edison, who used techniques to access the diffuse mode.

“Researchers have found that we have two fundamentally different modes of thinking… We’re familiar with focusing. It’s when you concentrate intently on something you’re trying to learn or to understand. But we’re not so familiar with diffuse thinking. Turns out that this more relaxed thinking style is related to a set of neural resting states.”

“So the bottom line is, when you’re learning something new, especially something that’s a little more difficult, your mind needs to be able to go back and forth between the two different learning modes. That’s what helps you learn effectively.”

- Chunking:

A chunk is a compact package of information, a mental leap that unites bits of information together through meaning. Neuroscientifically, chunks are pieces of information “bound together through meaning or use.”

Forming chunks makes information easier to remember and allows it to fit into the larger picture of what is being learned. It’s like converting a cumbersome computer file into a ZIP file.

The process of forming a chunk involves three key steps:

Focused Attention: Undivided attention on the information to be chunked. Distractions hinder this process. “The first step on chunking is simply to focus your undivided attention on the information you want to chunk.” Understanding: Grasping the basic idea. Understanding acts as “superglue” that holds underlying memory traces together. However, understanding alone doesn’t create a readily accessible chunk; practice is crucial. “The second step in chunking is to understand the basic idea you’re trying to chunk…” * Context and Practice: Seeing not just how to use a chunk, but also when to use it. This involves practicing with related and unrelated problems to understand the bigger picture. “The third step to chunking is gaining context, so you can see not just how, but also when to use this chunk.”

Chunking helps the brain run more efficiently by allowing access to the main idea without needing to remember all the underlying details.

A large library of well-practiced chunks is essential for expertise and facilitates problem-solving and creative linking of ideas. “The bigger and more well practiced your chunked mental library, whatever the subject you’re learning, the more easily you’ll be able to solve problems and figure out solutions.”

- Memory Systems:

The sources differentiate between Working Memory and Long-Term Memory.

Working Memory is the immediate and consciously processed information, centered in the prefrontal cortex. It has a limited capacity, believed to hold only about four chunks of information. It’s described as an “inefficient mental blackboard” that requires repetition to retain information. “Researchers used to think that our working memory could hold around seven items or chunks, but now it’s widely believed that the working memory is holds only about four chunks of information.”

Long-Term Memory is like a storage warehouse, immense in capacity but requiring practice and repetition to easily access information. Different types of long-term memories are stored in different brain regions. “The other form of memory, long term memory, is like a storage warehouse.”

Information moves from working memory to long-term memory through a process called consolidation, which is aided by repetition and sleep. Recalling a memory also changes it through reconsolidation.

Spaced repetition is a key technique for moving information into long-term memory. Repeating material over several days is significantly more effective than cramming it all into one session. “This technique involves repeating what you’re trying to retain, but what you want to do is space this repetition out… Extending your practice over several days does make a difference.”

- Combating Procrastination:

Procrastination is a habit triggered by a “cue” associated with something that causes “a tiny bit of unease.” The brain seeks to alleviate this discomfort by switching attention to something more pleasant, providing a temporary reward.

Procrastination can be understood as having four parts: the Cue, the Routine (the act of procrastinating), the Reward (temporary relief), and the Belief (underlying feelings about changing the habit).

A powerful tool to address procrastination is the Pomodoro Method: setting a timer for 25 minutes of focused work, followed by a short break and a reward. This technique focuses on the process (working for a set time) rather than the product (completing a task), which is less daunting and easier for the habitual part of the brain to engage with. “To prevent procrastination you want to avoid concentrating on product. Instead, your attention should be on building processes.”

Ways to increase the efficacy of the Pomodoro Method include eliminating distractions, working on least favourite assignments first (“Eat your frogs first”), sticking to the plan, and believing in your ability to overcome procrastination.

Rewiring the procrastination habit involves identifying the cue, planning a new routine (like using the Pomodoro), finding a genuine reward for sticking to the new routine, and changing your underlying belief about your ability to change.

- Illusions of Competence and Effective Study Strategies:

Illusions of Competence occur when students think they understand material but actually do not. This is often caused by ineffective study methods.

Common illusions include merely glancing at a problem’s solution, highlighting too much text, and rereading notes or textbooks without active recall. “Merely glancing at a solution and thinking you truly know it yourself is one of the most common illusions of competence in learning.”

Effective strategies to avoid these illusions and strengthen learning include: * Testing Yourself / Active Recall: This is crucial for determining whether you truly grasp an idea and knitting concepts into your neural circuitry. “A super helpful way to make sure you’re learning and not fooling yourself with illusions of competence, is to test yourself on whatever you’re learning.” * Practice: Consistent practice helps build and strengthen neural patterns. “Practice makes it permanent.” * Deliberate Practice: Focusing on what you find more difficult, rather than repeatedly solving problems you already know how to do. “This focusing on the more difficult material is called deliberate practice. It’s often what makes the difference between a good student and a great student.” * Interleaving: Mixing up your studies by working on different subjects or different types of problems within a subject. This helps you learn when to use different techniques and prevents Einstellung. “You can make your study time more valuable by interleaving, providing intelligent variety in your studies.” * Using Explanations and Analogies: Trying to explain a concept in simple terms, as if to a ten-year-old, or creating analogies helps to deeply encode the information. “Using an analogy really helps, like saying that the flow of electricity is like the flow of water.”

- Memory Techniques:

Creating Meaningful Groups: Simplifying material by grouping items, such as using acronyms. “Another key to memorization is to create meaningful groups that simplify the material.”

Visualisation and Analogies: Creating lively visual metaphors or analogies to represent concepts makes them more memorable and helps connect to the brain’s visual-spatial centres. “One of the best things you can do to not only remember, but understand concepts, is to create a metaphor or analogy for them; often the more visual the better.”

Memory Palace Technique: A powerful method for remembering unrelated items by associating them with specific locations in a familiar place (like your home). “The memory palace technique is a particularly powerful way of grouping things you want to remember. It involves calling to mind a familiar place… and using it as a sort of a visual notepad where you can deposit the concept images that you want to remember.”

- Overlearning and Einstellung:

Overlearning is continuing to study or practice something after you’ve mastered it in a single session. While a little can be useful for automaticity (e.g., in sports or public speaking), excessive repetitive overlearning in one session is inefficient and can contribute to illusions of competence by focusing only on easy material. “A little of this is useful and necessary, but continuing to study or practice after you’ve mastered what you can in the session is called overlearning.”

Einstellung is a phenomenon where your initial thought or a strongly developed neural pattern prevents you from finding a better idea or solution. It’s like being stuck in a rut of thinking. “In this phenomenon, your initial simple thought, an idea you already have in mind or a neural pattern you’ve already developed and strengthened, may prevent a better idea or solution from being found.” Using diffuse mode thinking, metaphors, and the hard start-jump to easy test technique can help overcome Einstellung.

- Importance of Sleep and Exercise:

Sleep is critical for learning and memory consolidation. During sleep, the brain repeats patterns and pieces together solutions. It helps to weave loose threads of experience into memory. “You will learn in this first week how to take advantage of your unconscious mind, and also sleep, to make it easier to learn new things and solve problems.” (Lecture Transcript 1, p. 9) Not getting enough sleep “allows toxins to build up in the brain that disrupt the neural connections you need to think quickly and well.”

Physical exercise is presented as one of the best gifts for the brain. It helps new neurons in the hippocampus survive, aiding in learning new things. “Exercise is by far more effective than any drug on the market today to help you learn better.”

- Mindset and Belief:

Belief in your ability to learn is crucial. Overcoming negative self-perceptions, such as believing you “don’t have the math gene,” is important for success. “Believe that you can conquer procrastination! As with any goal, you will only accomplish it if you believe that you can.”

Changing your thoughts can change your life, as exemplified by Santiago Ramón y Cajal, who overcame being a “troublemaker” to become a Nobel Prize winner through perseverance and flexibility. “It seems people can enhance the development of their neuronal circuits by practicing thoughts that use those neurons.” (Lecture Transcript 1, p. 60)

Perseverance is highlighted as a virtue, particularly for those who may not perceive themselves as naturally brilliant.

Reframing negative occurrences and seeing problems as opportunities can help maintain a positive mindset. “Reframing is a mental trick that allows you to find the positive ways to think about a negative occurrence.”

- Test Taking Strategies:

•

Preparation is key, including building a strong mental library of chunks.

•

The Hard Start – Jump to Easy technique involves starting with a difficult problem, but moving away within a minute or two if stuck, then working on easier problems, and returning to the harder ones later. This technique uses the diffuse mode and helps avoid Einstellung. “The answer is to start with the hard problems but quickly jump to the easy ones.”

•

Checking your work from a big-picture perspective is essential to catch errors, especially as the left hemisphere can be overly confident. “Your mind can trick you into thinking that what you’ve done is correct even if it isn’t.”

•

Managing test anxiety involves reinterpreting stress symptoms as excitement and using deep breathing techniques. “If you shift your thinking from, this test has made me afraid, to this test has got me excited to do my best. It can really improve your performance.”

•

Having a “Plan B” for alternative career paths can help alleviate the fear of not achieving a desired grade.

Conclusion:

The provided sources offer a comprehensive overview of effective learning strategies grounded in basic principles of cognitive neuroscience. By understanding how the brain functions in focused and diffuse modes, forming strong mental chunks, utilising effective memory techniques like spaced repetition and the memory palace, actively combating procrastination, avoiding illusions of competence, and adopting a growth mindset, learners can significantly improve their ability to master tough subjects. The emphasis on process over product, deliberate practice, and strategic test-taking provides practical tools for enhanced academic performance and lifelong learning.